Hidden Door CEO: AI debate has to do with “worth,” not tech

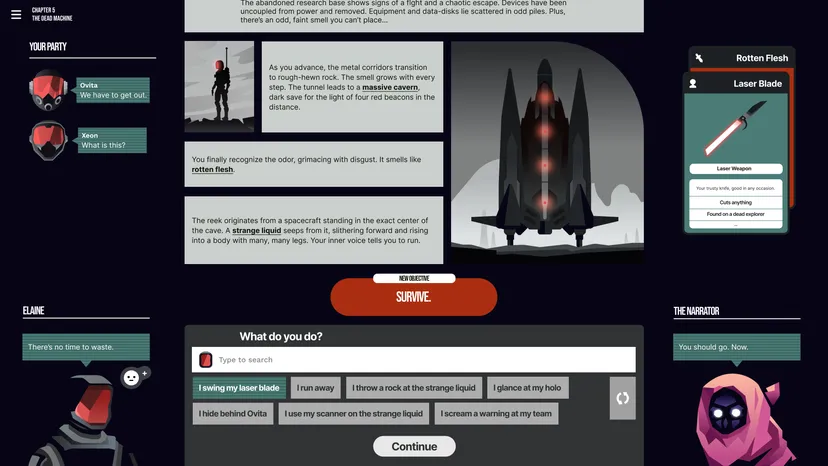

The PC Gaming Show in June saw the official premiere of Hidden Door, a generative AI story platform, to what could be described as a hostile audience. Long-running comic bits mocked the results of programmes like Midjourney and ChatGPT while the rest of the broadcast promoted new games added to Steam or the Epic Game Store every day.

The premiere wasn’t exactly the ideal setting for Hidden Door. Having a man with a Southie accent as the opening act made the whole thing feel like watching a standup regular talking about how many people Boston attracts. Oof.

Even if the creator’s pitch had a rocky landing, Hidden Door (both the designer and the game have the same moniker) nonetheless managed to pique my interest. It’s a platform based on refined massive language designs (LLMs) that was inspired by tabletop RPGs, and it doesn’t show any of the red flags that have worried me about prior generative AI developments.

The creators insist they have no plans to alter the system or reduce author compensation. Hidden Door is an amalgamation of various ideas that seem to alleviate ChatGPT’s plagiarism problems. Perhaps most importantly, it’s being advertised with an appropriate amount of hype. It’s not a step on the road to AI, but it’s a nice way to play impromptu adventures with your pals.

The CEO of Hidden Door, Hilary Mason, seems familiar with the scepticism of generative AI that has kept the program’s humour alive during an interview two days after the PC Gaming Show. She also offered an interesting perspective on the numerous arguments around the technology, namely that the ire directed at AI tools is not directed at the technology per se but rather at the value it provides and the people who stand to gain from it.

Hidden Door’s CEO has actually been explore artificial intelligence for over a years

Mason’s experience as a founder of a video game firm is relevant to understanding her stance on the issue. She worked as an information researcher for years, dealing with various device learning-informed inventions, before transitioning into the field of computer games, as she explained at the MIT Gaming Industry Conference’s AI panel a few months ago.

She also quipped at the panel that her first company was born from a DARPA-funded research project in which she “broke Wow’s regards to service to gain access to real-time habits information on gamer intent.” A market built on the ruthless quest of data, obtained either with disregard for the data’s original owners or just out of an obsessive notion that data must be complimentary, is a near-perfect tale for this discussion of generative AI.

When I brought up that story again and asked Mason to explain the changes in her perspective on information security, she seemed a little embarrassed. She responded, “For anything, I remained in my twenties and was really adventurous. Another issue, we stayed in a design of structure maker learning systems that could never beat whoever was creating the underlying data. That’s been the gold standard in the industry for the past two decades.

It’s kind of a “oh shit” moment for a lot of people, but “only now have we scaled the capability of those systems to compete directly with individuals developing the underlying information.”

She claimed that she has “grown and developed” since those “wow” days, and that she would not advocate for the same strategy now.

Her remark about AI “completing” with the information’s creators captures the market’s current worry about generative AI. MidJourney and ChatGPT, for example, were built on publicly available academic datasets that scraped web content with the promise that it would be used solely for research purposes, only to later switch to a for-profit business model in order to attract equity capital funding.

Mason’s argument takes form through the recognition of competition: generative AI technologies can generate monetary value. And the fights over its application, whether at game development studios, the Hollywood author’s strike, or the classroom, all revolve around who gets to reap the benefits of that value.

Her explanation summed up the gist of the conversation. Infuriatingly, “you have this new thing that is completing straight with them by using their work without consent,” which adds to the “great deal of things that have actually been established to squeeze creative people over the last years.”

Mason, who has spent years designing products with embedded machine learning, does not find this technology “innately bothersome,” but he does agree that how the technology is being used and who is benefiting directly drives the emotions behind the conversation at the PC Gaming Show.

Authors and developers working with the platform will be compensated, and any derivative works that draw inspiration from their worlds will be “additive,” rather than a replacement.

What is generative AI even great for in video games?

Mason was also able to shed light on how the realm of video game development might stand to benefit from generative AI technology. She admitted that most of the talk has centred on how to integrate generative AI tools into preexisting pipelines to produce traditional video games more quickly and on a larger scale.

She has a keen interest in creating new genres of games, namely those that rely heavily on a complex linguistic framework. Since a tool designer for studios seemed like a safer business proposition, I questioned why she decided to focus on the consumer market instead.

According to her, “owning the entire [tech] stack” is essential when building a great product. “It’s the only way to create something that is a brand-new kind of experience, and it’s also the most enthusiastic way to understand if [your idea] is an excellent experience,” he added.

It’s worth noting that Mason had the epiphany that her machine-learning studies could be turned into a fun game. Mason’s previous company, Fast Forward Labs, produced text tools based on machine learning for corporate clients. Think about automated chatbots for client service, summarization tools for product dealers, and even technologies that could summarise a newspaper piece.

In these industries, accuracy is of the utmost importance, but unfortunately, machine learning methods often fail to deliver. In such a setting, “the way these designs hallucinate and anticipate [incorrect facts] is a liability,” the authors write. I saw enormous potential in facilitating access to cutting-edge equipment.

By using the term “innovative tooling,” Mason emphasised, she does not mean to imply that the tools themselves are creative. Only that there might be a way to lessen resistance to creative endeavours.

The transition from “hallucinations” to “enjoyable video game” is fascinating because it brings to light a facet of many outlandish, hype-driven AI employment that is often overlooked. The idea that generative AI technologies will be used to alter conventional methods of media production has captured the attention of the equity capital world. It does not appear to be particularly good at it, and the promise that it eventually will be ignores the innovation’s fundamental flaws. (Have you ever noticed that there aren’t many depictions of weapons in Midjourney artwork? It does a poor job of depicting firearms.

However, despite being poor at duplicating the real deal, these tools excel at creating stunning images that your brain immediately flags as “incorrect” despite their frightening beauty. It’s a shame that damaged artwork can still evoke admiration.

Mason did want to stress that these tools also have a wide variety of security issues, as generative AI systems are constrained by the biases of their creators and cannot naturally recognise when they are displaying inappropriate or destructive content. The product that would become Hidden Door was refined in part because of strict security requirements.

She elaborated, saying, “We began with an architecture created around security and controllability, and we recognised that offers us both the capability to offer our gamers a secure experience and the capability to work with authors and developers to supply them the controllability.” She also recalled that the generative text designs aren’t great at making up story arcs for players, and that a different approach is being fine-tuned to promote rising tension and keep players engaged in the game.

The security requirements for Hidden Door gave us an opening to discuss the peril of depending on an AI storyteller to relay tales set in foreboding or violent environments. Mason explained that the word “Nazi” cannot be used by default on the platform (to better prevent white supremacy from sneaking onto the platform), but that it might be allowed in certain contexts, such as an Indiana Jones-style experience in which players are punching Nazis left and right.

Ask my old Dungeons & Dragons party, who tried to seduce every opponent the GM threw at us, about how gamers in tabletop-type settings typically want to explore the darker or more sensual sides of the human experience. Can those players really push Hidden Door to its limits?

For the most part, “we let our developers and our authors whose IP we’re embracing set where they desire those limits to be,” as Mason put it. The goal of Hidden Door is, once again, to try and allow the creatives select where the limits of the story are, even though there are certain types of content the platform would never consider hosting (such as sexualized material involving kids).

Mason remarked that her colleagues had to deal with some reasonable gamer concerns even in a copyright-free setting like Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz (the inspiration for the actual playable tale world in the video game). Someone in our Discord server recently requested whether they might kiss Glinda the Good Witch, she said. She initially said, “Well, you could, but she (Glinda) may not like that.”

The company may have allowed the kiss but imposed strict limits on how it could develop into anything more sexual.

Calling it “AI” assists corporations sidetrack from potential labor theft

Even the abbreviation “AI” can be used to obscure the true financial impact of the innovation by conjuring up the danger of imaginary intense AI beings like Skynet, SHODAN, Lore, etc., as Mason pointed out, which is an interesting point about the “worth” developed by generative AI.

She does not believe the technology she is working with is capable of producing artificial intelligence and even tried to market it under a different name at her former company. She recalled, “I fought strongly to use the word ‘artificial intelligence’ and not ‘expert system. I tried my hand at ‘device intelligence,’ but the market didn’t go for it. (Regardless of her reluctance, we must bear in mind that Hidden Door’s advertising places heavy emphasis on the efficacy of “narrative AI”).

Her reluctance to use the phrase is supported by the doomsday predictions pushed by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and leading Twit Elon Musk. When asked about the effects of growing such systems on the economy, she said, “I find that discussion is typically disruptive from the genuine damages of scaling these systems.” “I’d personally encourage people to focus on the moment we’re in and the impact on labour markets, the impact on different tasks, and how we think about dispersing the benefits relatively,” the author.

Launching Hidden Door during the AI-soaked PC Gaming Show captures the peculiar time in which we find ourselves. There is legitimate worry that generative AI may strip artists of their livelihood while creating value for businesses. There are also designers and toolmakers investigating the technology’s limitations to improve it.

One is not superior to the other, but if the harm caused by generative AI innovation persists, people may become less receptive to its widespread application in everyday life.